-------

UPCOMING EVENTS:

HOLM AUDIO

Music Matters Event.

Thursday, October 20 2026

11AM to 9PM

Goodies given away.

Meet Charles Kirmuss.

Reservations required: (630) 663 1298

Also Reps from KEF, Luxman, Nordost, and Rega will be present.

Show specials and drawings.

Bring a record for us to restore!

--------

Florida International Audio Expo

Feb 20 - 22, 2026 in Tampa Florida

Sheraton Tampa Brandon

10221 Princess Palm Ave, Tampa, FL 33610

Bring a record for us to restore.

----

About the Kirmuss process using record ionization.

Not a surface shing system, rather a record groove restoration system. Used once in the life of a record.

TESTIMONIAL:

“After 1 year of testing: "Best of all when I played it, (after record restoration), HOLY CRAP!“, “The top end fully restored,the backgrounds were super quiet, transients were sharpened, the inner detail in Peter Townsend’s rhythm guitar strings (Tommy) produced an almost new listening experience.” (2019) “While skeptical at first, Charles Kirmuss has proven to me everything he advertises is true and I cannot disprove. ” “I wholeheartedly endorse the Kirmuss System”. “It does not clean, it does restore!”..

“AND ITS AFFORDABLE!” Recommended. Restores, not just surface cleans.” Michael Fremer, TrackingAngle.com/TAS (2024)

RESEARCH:

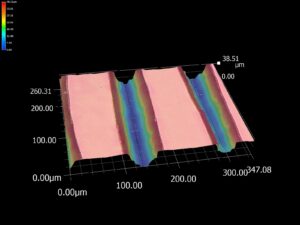

1) Do take a look at the latest videos of the Kirmuss process in action, unscripted. Recorded by "An Aussie Audiophile" ( and presented on his YouTube channel), (link above), see the proof of record restoration and how we can both quantitatively and qualitatively measure the effectiveness of any record cleaning process. AND PROVE RECORD RESTORATION.

On our KirmussAudio YouTube channel. True A-B before and after restoration testing.

Two short video clips show two records that were brought in by their owners at the CONSAM and Kirmuss-Margules audio event in Mexico City this past November. Records brought in for us to restore were previously cleaned using a vacuum based cleaning machine and a purported 120KHz ultrasonic. As we do at all events, a before and after auditioning was performed. In the video: Connected was a spectrum analyzer. See, hear and feel (and see) the results of Kirmuss Record Groove Restoration. The KirmussAudio KA-RC-1 is not a surface cleaner or shiner.

2) How does your current cleaning process compare?

Do current processes do anything more than just to shine a record?

------

3) WARRANTY:

Unlike peers,

We state and guarantee a 1.3 to 1.4 dB gain over floor and an 8% increase in frequency/spectral response in new pressings. Results vary based on the Presser and PVC used. Between 3 and at times upward plus dB gain over floor and heard and measured an 18-28% increase in frequency response in our processing vintage records of provenance unknown.

4) THE KIRMUSS PROCESS SEES ONE CYCLE THE RECORD IN AND OUT OF THE MACHINE SEVERAL TIMES USING 2 or 4 MINUTE CYCLES.

The magic:

An ionizing agent is sprayed on the record to remove:

First cycle: Removed: Films left over from Groove Glide and other agents;

Second cycle: The scratches that are present on the film of the outgassing of the plasticizer while the record is in its sleeve for decades. (Heard as clicks / ticks);

Third, Fourth Cycles: The Removal of the release agent (pressing oil) that surfaces during the pressing process that allows the record to "pop out" of the stamper. As this oil cools, contaminants land on this cooling oil and get fused into the groove, home to those unwanted and nasty "pops" heard".

The needle finally discovers the hidden music, tone, timbre, resonance, harmonics, in effect the fundamentals of music as recorded live.

5) TRUE CAVITATION:

Measured in Cavins or Watts of cavitational energy from the edge of the record to the dead wax area, and between all records. ( 810 Cavins +/- 10%). Note without changing the charge of the record to be opposite to that of water, one cannot truly offer the results as the Kirmuss process does.